This essay originally appeared in the February edition of

, which is a banger as always. You can read the entire issue here.Thanks to Uncle Steady for being my partner-in-crime on these strike missions and our families for not laughing too hard at us… this year we’re definitely bringing home dinner!

Hunter S. Thompson, in his essay “The Kentucky Derby is Decadent and Depraved,” popularized the type of writing now known as “Gonzo Journalism.” Written in the first-person, often sensationalized, with the truth becoming fluid, Gonzo is a stark contrast to traditional journalism1. Despite claims to the contrary, Gonzo journalism is not dead, it’s just been relegated to dispatches from Vice magazine: well intended, but ultimately a wink-and-a-nod, an I’m doing this, but isn’t it ironic? type of writing that becomes more about the author than it does the subject2.

I’m not interested in that type of writing, nor living, for that matter3. I want to do things for more than the sake of just doing things, experiencing them, not just relating them as a good yarn. I don’t want a host of experiences I can bring up to make myself sound more adventurous than I might actually be. I want to actually live that adventure.

Which is how I ended up, on a lark, in a dive shop in Egg Harbor, NJ, trying on dive masks and debating between an 80 and 100cm Rob Allen Cobia speargun. How, with my brother-in-law, Uncle Steady, I ended up swimming swimming a half-mile off the Long Beach Island shoreline, fighting the currents, looking for a 100-year old shipwreck, where there might be fish, looking up to see a lifeguard paddling, exhaustedly, asking what-in-the-actual-heck we were doing out this far from shore.

“Spearfishing, sir. There’s supposed to be a wreck around here.”

“Never heard of it. See any fish?”

“Well, not yet.”

“Huh. Are you guys professionals or something?”

“I wouldn’t go as far as to call ourselves that.”

“Weird answer. Well, we can’t see you from the lifeguard tower. You should probably swim in before you get caught up in a pleasure-cruiser’s propeller. That’s a tough way to go.”

“Yes, sir. I imagine so. Thanks.”

A few weeks later, after finishing the week in New Jersey without seeing a single spearable fish, Uncle Steady and I trekked again out to the North Shore of Massachusetts and, between our kids’ naps, slipped down across rocks and seaweed into a cove reputed to host not only flounder, tog, and maybe a weakfish, but also some lobster.

Earlier that morning, at different beach, with wives, kids, beach toys, and all manner of gear, (except for, of course, spearfishing gear) we watched what at first we thought was a remnant Stellar’s Sea Cow, but was actually an old lady suited up in full SCUBA gear, emerge from the water with nigh on a dozen lobsters wriggling in her bag.

At the sight of that, we thought to ourselves, “how hard can this be?”

Certainly, we, two strapping former collegiate swimmers, outfitted with entry-level equipment and no lobstering experience whatsoever, could surely match the output of a species that went extinct before the founding of America — or at least that of a geriatric lobsterwoman?

So down we descend into water, full of optimism and high hopes. (“Don’t eat too much for lunch — we’ll be bringing home plenty for dinner!”) Swimming out, gazing toward the rocky shoreline, we enter the aquatic realm of fish, watching for a glint of sun against a fin, the scuttle of a crustacean on the sea bottom.

I hug the rocky edge of the cove, peering into crevices, looking for sign of one of the three fish I feel comfortable identifying by sight, but more focused on lobsters. Uncle Steady, more optimistic than even me, heads out further toward the open ocean, hunting the sand for flounder. Stopping to drain the water from my mask — not accounting earlier for the width of my wetsuit hood — I notice Uncle Steady waving me excitedly over.

“I found a flounder! I’m going to head back down to spear it.”

“Groovy!”

“Hey, what did the guy at the dive shop say about braining a flounder?”

“Stab it perpendicular to its body — otherwise it will swim away and slice itself in half.”

And down he goes, only to resurface moments later.

“Shoot. I think I lost it.”

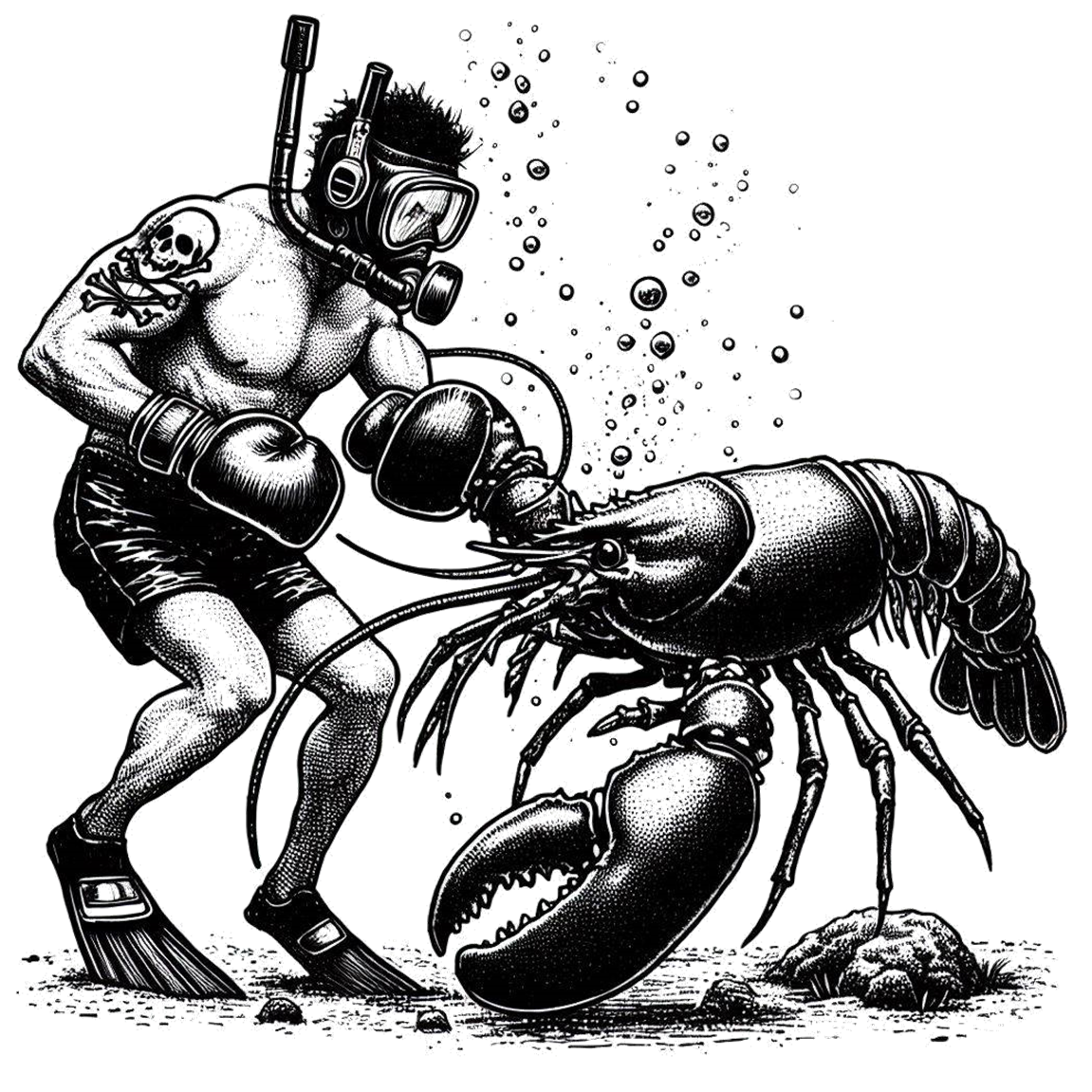

I swim off to let Steady try to relocate dinner, hoping to get back amidst the crustaceans. After cruising for a few minutes, I see movement. A lobster, on the hunt for his own meal. I let the current drift me over top of him, noticing that my quarry is missing his front left claw. I do a quick visual gauge of his size4. Going purely on instinct, I kick down, and the lobster rears back.

Muhammad Ali famously described himself as floating like a butterfly, stinging like a bee. He could have perhaps as accurately said he swam and pinched like a lobster. Despite having only a single claw, this lobster clicked and clacked, sprinted backward and away from my oncoming hand5. Fortunately, I found him out in the relative open, leaving him with no clear escape routes. I grab him on my first attempt. A more accurate measurement with my clenched fist reveals that the lobster as just over the legal minimum. Given his missing appendage and the fact he likely wouldn’t survive in the wilds of the ocean much longer, I stuff him in my bag.

As I swim over toward Steady, I notice that he is flounderless — and floundering. His lips are bright blue and teeth chattering, perhaps owing to the fact he chose to forgo wearing a wetsuit. After showing him my catch — “It’s bigger than it looks, I swear!” — I ask if he’s okay.

“Definitely… just… a little… cold.”

His hypothermia and my bounty seem good enough reason to head back to shore and home.

Now, I have eaten plenty of lobster in my life, in all manner of preparations. I’ve had lobster boiled, grilled, sauteed, and raw. I’ve had lobster rolls, lobster ravioli, lobster risotto, and lobster bisque. But much like the best steak you’ll ever have is the tenderloin from a freshly harvested deer, the best lobster you’ll ever have is one steamed, just after it’s been caught, in the same water it was just swimming in. And while the meal may have been meager — us having to head to the seafood spot just up the road from our house after cleaning our plates — I can with absolute certainty it was the most satisfying lobster I’ve ever eaten.

Here’s to living and eating your own adventure.

P.S. — Astute readers, especially who read via the website, might notice a slight brand of the logos. Let me know what you think! Paid subscribers, look out for an email from me soon with some top secret info on this year’s reader gift, which is directly related — and for everyone else, there’s still time to sign up to get in on the action!

You can read more about logo in the recently updated “About” section.

But, as Thompson himself said “absolute truth is a very rare and dangerous commodity in the context of professional journalism.”

Which, if we’re being perfectly honest, is true of most “content” these days, anyway.

I want to write as radically as I live and eat.

In Massachusetts, a lobster’s body must measure at least 3 ⅜ ” and at most 5 ¼”.

Massachusetts does not allow the taking of lobsters by spear, only hand-harvesting.

Love, love, love this allegory! What an adventure! I can just picture it perfectly.

So, so, so glad you got that lobster! Maybe one day when you are a geriatric old man, you will emerge from the water with a dozen lobsters in a net...but for now, it would be great to say you and Uncle caught six between you, and all with both claws.

I love you, my fearless young man!

I was kind of thinking Best Case Scenario, but didn't want to be overly optimistic.